My parents always said they moved to the States so I could have a better education, so that’s where I focused—Leslie Gutierrez.

Leslie Gutierrez

When she was a baby, Leslie’s family moved from Mexico to Calhoun because of the job opportunities in carpet manufacturing. Growing up, Leslie focused on her studies and always supported her parents in navigating the job market and with language. She was the first member of her family to go to college.

Learning in a New Language

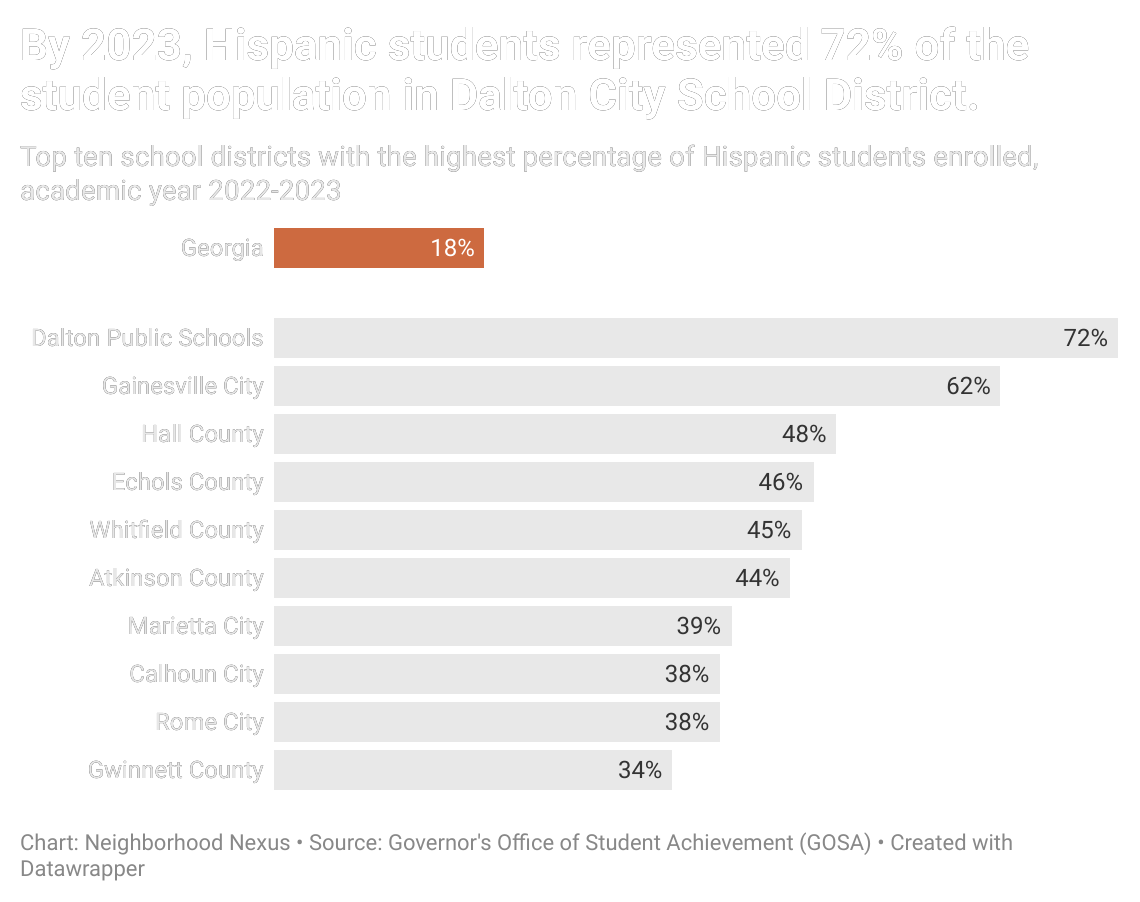

In 2021, Georgia had the sixth-largest population of English Learners in the nation49, with and estimate of 80% of these students being Latino50. English Learners are those students whose first language isn’t English and who are learning English as a second language.

Many Latino students’ parents are immigrants who had limited educational resources in their home countries. In Georgia, the average exit rate for students in the ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) program during the 2022-2023 school year was 13%, but this varied significantly by district19.

While these low rates are undoubtedly influenced by factors such as families relocating for job opportunities, housing insecurity, and immigration challenges, they remain disturbingly low and should be addressed at a policy level.

For example, Richmond School District’s ESOL exit rate in 2023 was just 3%, while some state charter schools had a rate of 30%. In the metro Atlanta area, the exit rates were particularly low—Atlanta Public Schools was at 5.5%, and DeKalb County School District was at 6%19.

An ESOL exit rate indicates the percentage of students considered proficient in English and no longer needing language support.

Additionally, reports reveal that English Learners in Georgia, like Black and African American students, face disproportionate disciplinary actions20. Despite federal laws and guidelines for language access, only Atlanta Public Schools have established a language access policy at the governance level. As a result, it falls on parents and nonprofit organizations to navigate these challenges and obtain consistent information, especially given the significant changes that can occur with political and administrative transitions.

Despite their strong commitment to education, Latino children in Georgia’s K-12 system often face discrimination and barriers in the classroom21. America Gruner, Founder and CEO of the Coalición de Lideres Latinos (CLILA), an advocacy organization that works to advance human and civil rights for Georgia’s Latino community, points out that some schools used to limit access for kids who didn’t speak English, sending them to alternative schools that were unprepared to help them succeed. Based on her experience as a leader in her community for over 30 years, Gruner shares that these decisions were often made solely because the children were Latino, not considering where their families lived. In some counties, barriers to accessing information can cause many Latino children to remain in ESOL programs longer than necessary, impacting their long-term academic development.

Interviews for this report revealed that many Latino students were placed in ESOL classes without their parent’s consent and were sometimes even kept out of gifted or advanced classes simply because of their background. In addition, many schools focused on Latino students have concentrated on teaching technical skills for jobs rather than offering a well-rounded education. Even today, schools with large Latino populations often prioritize these technical skills over a more comprehensive learning experience.

On the other hand, Maritza Morelli, Executive Director and Founder of Los Niños Primero, comments that children of families who have recently migrated often experience high levels of stress as they adapt to a new education system and language, while also coping with the violence they may have escaped. Based on her experience providing educational support to underserved Latino students, parents frequently struggle to engage with schools due to language barriers and a lack of resources and support that would enable them to participate fully in their children’s education.

Educational Outcomes

These barriers that our children face can significantly influence families’ decisions about pursuing higher education, leading to delayed postsecondary graduation or even dropping out after enrolling. In 2023, 77.6% of Latino students graduated on time. However, this rate drops to 66% for English Learners. For comparison, 94% of Asian and Pacific Islander students, 87.1% of white students, 82.5% of multiracial students, and 83.7% of Black or African American students graduated on time19.

In the 2022-23 school year, only 28.1% of Hispanic students scored proficient or higher in 3rd grade English Language Arts, compared to 38.7% of all students and 52% of white students. Similarly, 28.6% of Hispanic students achieved proficiency in 8th-grade Math, while 36.3% of all students and 51.8% of white students reached this level19.

Many Latino children who discontinue their education do so after high school, often to work to support their families’ short-term economic needs. About 21% of Latino adults in Georgia hold a Bachelor's degree or higher, compared to 33.6% of the overall population1.

I was the first member of my family to experience K-12 in the US. I had to learn what a GPA was, etc.

Luis Hernandez

Luis is a U-Lead graduate. He moved from Guanajuato, Mexico, when he was nine and learned English while he was in elementary school.

The CHallenge of Continuing Education

Latinos’ strong belief in the value of education is clearly reflected in the data. Latino parents engage enthusiastically in providing resources and support to their children, even when they have not completed their own education due to their own barriers. We see it as a vital pathway to prosperity and a brighter future. For example, three times as many Latinos aged 25 and older lack a high school diploma than the average Georgian. Yet, their children are enrolled in nursery, preschool, or K-12 programs at a higher rate than the state average1.

The Governor’s Office for Student Achievement (GOSA) reports an 11-point gap in college enrollment between the state average and Latino students within 16 months after graduation19. In general, Latino students face limited options for higher education outside urban areas and traditional university locations in the state.

The top institutions awarding post-secondary degrees to Latinos in Georgia as of 2021 were22:

- Kennesaw State University

- Georgia State University

- Georgia Gwinnett College

- University of North Georgia

- University of Georgia

For associate degrees22:

- Georgia State University-Perimeter College

- University of North Georgia

- Georgia Military College

- Georgia Highlands College

- Gwinnett Technical College

Encouraging kids to leave school early for work is becoming less common as parents now prefer to work extra hours or days to allow their children to continue their education. However, persistent financial pressures and limited culturally appropriate support make this desire challenging to fulfill, pushing Latino students to abandon school to support their families by working or caring for younger siblings.

These pressures not only affected educational outcomes but the overall school experience for Latino children.

I remember all my schoolmates' parents took their kids on field trips, but mine always worked, so I wasn't doing that.

Leslie Gutierrez

In high school, Leslie realized the limitations she had because of her immigration status when she couldn’t get her driver’s license at 15, like all of her friends who started driving to school. It wasn’t until she applied for DACA that she could take the test and get her license. For a long time, she said she just didn't want to drive to avoid more questions.

Luis was forced to take two years before accessing higher education due to economic barriers and a lack of federal aid. Through hard work, he earned a full scholarship to Berry College under the Bonner Scholars Program, engaging in 1,500 hours of community service.

Undocumented individuals and certain lawful residents, such as those with Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), are banned from attending three major public higher education institutions in Georgia: the University of Georgia, Georgia Tech, and Georgia College and State University. This exclusionary policy significantly impacts representation in these institutions.

Even if they can enroll, DACA recipients do not qualify for in-state tuition. Thus, they face tuition costs two to four times higher than those for other Georgia students who are deemed “lawfully present.”

I didn't have plans to go to higher education, much less think about how my immigration status would impact that later. As a first-generation student, experiencing all of this was very tough. Nobody in my family knew how to guide me, and I didn't know what questions to ask.

Luis Gutierrez

This lack of access and the financial burden imposed on many Latino families create barriers to wealth-building and threaten self-sufficiency and wage growth. Additionally, it increases the risk of crippling debt for families prioritizing education but already struggling financially.

Finding Support

Because of the barriers she faced as a DACA recipient, Leslie attended a private university where she got a scholarship thanks to her excellent academic record. She found this support after revealing her status to a high school teacher who guided her, even after her parents always advised her to keep it a secret for fear of exposure and discrimination. Years later, she went through all this effort again to earn another scholarship and continue her education as a graduate student.

For children, financial pressures and educational institutions’ slowness to adapt to the fast growth of Latinos foster feelings of isolation. The lack of support means they must navigate external agencies like nonprofits for academic support and guidance.

I received a lot of support from the U-Lead program, which helped me get good SAT scores. Later, I found economic support from private universities.

Luis Hernandez

Additionally, Latino children often deal with unique pressures as they balance their schoolwork while helping their parents adjust to life in the United States. Many act as language and cultural translators, helping their families find services and opportunities.

The truth is that immigration status and language significantly limit access to financial support and other essential services that impact not only the education of Latinos but many aspects of daily living. As a result, many families turn to community organizations for support, relying on these resources to navigate challenges and find opportunities that might otherwise remain out of reach.